In the early 20th century when there was a growing popularity of

chop suey and chow mein among Americans, two enterprising University of

Michigan students,Wally Smith and Ilhan New, neither of whom were

Chinese, hit upon the idea of creating and mass marketing a line of

prepackaged Chinese foods. Thus, La Choy, a coined name to generate

the feeling that the foods were ‘oriental’ was born in 1922. Wally

Smith, owner of a grocery store in Detroit wanted to sell fresh bean

sprouts. His friend, Illian New, a Korean American, was knowledgable

about how to grow bean sprouts, and they came up with the idea of

canning bean sprouts in glass jars. They expanded their canned products

to include a variety of Oriental vegetables using metal cans.

Newspaper

articles gave publicity to their products, such as one in 1929 telling

the public that these products now allowed “anyone to explore the

strangely delicious (italics mine) food.”

Today,

sales of La Choy and other brands of prepackaged Chinese food

ingredients have declined sharply, having been displaced by better

alternatives, but one could argue that La Choy contributed to its own

decline by popularizing home prepared Chinese food. As Jacqueline

Newman, editor of Flavor and Fortune, a periodical devoted to Chinese

cuisine, pointed out that in the 1920s, few non-Chinese knew how to

prepare Chinese dishes at home and that the introduction of La Choy

canned Chinese ingredients made a significant contribution to the

interest among non-Chinese in cooking Chinese food, admittedly limited

in scope, at home.

La Choy cleverly promoted their products by publishing free recipes booklets to guide the consumer, as shown below.

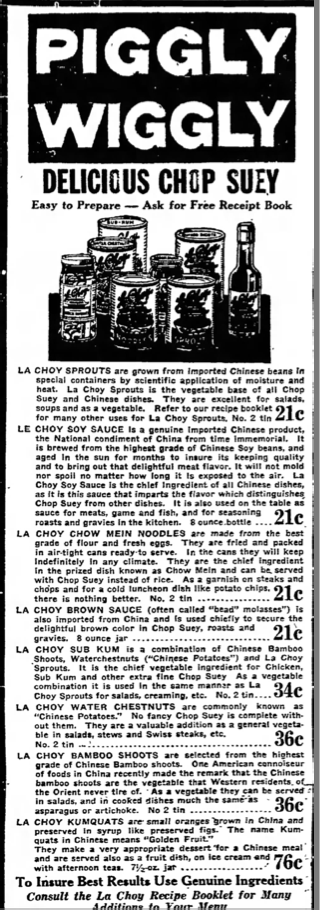

Ads of many grocery stores such as a chain in the South, Piggly Wiggly, prominently promoted La Choy products.

Whether

by chance, a touch of humor, or with malice aforethought, here are two

grocery store ads that placed LaChoy (and a later brand of prepackaged

Chinese foods, Chun King) next to dog food promotion. (Oddly, this La

Choy ad appeared in 1914, which precedes the 1922 founding of the La

Choy company)

An

ad in 1973 promoted “Oriental alternatives”…to American food, with the

slogan, Why not swing American with LaChoy? Discount coupons were an

added incentive.

An

ad focusing on the male-dominant Chinese society also encouraged

non-Chinese to have “a delightful change” from their usual cuisine by

having La Choy for dinner.

Chun

King, a rival to La Choy in the 1940s, was a line of canned Chinese

food products founded by Jeno Paulucci, the creator of Jeno's Pizza

Rolls and frozen pizza.

One of its ads below also emphasized

“Oriental for New Mood in Food” to encourage trying something different

from the usual meal. It also used celebrities such as Arthur Godrey to

plug their products, offered fashion news, and even discounts on nylons.

Sweepstakes with prizes such as trips to Hawaii also were offered by

Chun King.

Chun King promoted its line of Chinese foods sing a variety of

innovative and humorous ads created by a master of comedic parodies,

Stan Freberg,

Video of a Chun King ad:

"Break the American food habit of eating the same old thing every night."

"Would it hurt anyone of us to try something different tonight like chow mein?"

The

peak for the prepackage Chinese foods was sometime in the 1960s. By

the 1980s, larger corporations acquired smaller companies such as La

Choy. Chun King was purchased by ConAgra during the late 1980s, it

merged some of its product line with La Choy.

After retiring from a 40-year career as a psychology professor, I published 4 books about Chinese immigrants that detail the history of their laundries, grocery stores, and family restaurants in the U. S. and Canada.

After retiring from a 40-year career as a psychology professor, I published 4 books about Chinese immigrants that detail the history of their laundries, grocery stores, and family restaurants in the U. S. and Canada.