Life Working in Chinese Restaurants

October 15, 2019

When people dine in restaurants, however elegant or humble, Chinese or other cuisine, they rarely think about the kitchen and the conditions under which the restaurant staff toil to serve the orders from the patrons. It is hot, especially for the cooks, crowded with wait staff and kitchen help rushing around in tight quarters to serve meals in a timely manner.

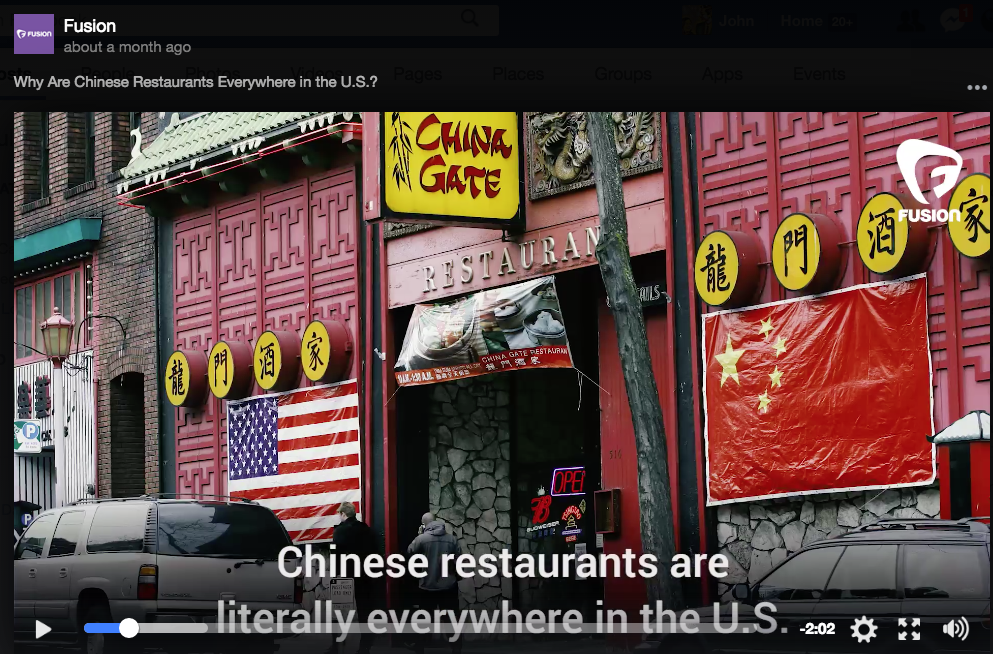

In Chinese, and probably in other ethnic restaurants, many of the workers are immigrants who find short-term employment through an underground network. Their ability to speak or understand English may be limited or non existent. Working long hours, mostly on their feet, they earn minimal pay with no fringe benefits and are vulnerable to exploitation by restaurant owners. They may have left families back in China and send part of their earnings back to support them..

A 2014 article by journalist Lauren Hilgers provided an in-depth and sympathetic examination of the plight of "underground workers" in several Chinese restaurants in the New York City area. Inspired by Hilgers' article in New Yorker Magazine, another journalist, Katie Salisbury, herself the grand daughter of a Chinese immigrant restaurateur, interviewed Chinese immigrant restaurant workers for an online report in 2018.

A cook sent Salisbury a documentary with English subtitles about the lives of Chinese immigrant restaurant workers portrayed in a poignant 2013 documentary on YouTube, Floating Days.

Salisbury presented a detailed and personal account of Chinese restaurant worker lives that follows a young Chinese immigrant who works at a takeout that reveals the dark side of the American dream: exhaustion, isolation, disillusionment, and a growing sense of frustration and aimlessness. In one scene, a cashier describes her life in a nutshell: “The restaurant is my stove. Home is my pillow.” That phrase has become a kind of sardonic mantra within the restaurant-worker community.

In Chinese, and probably in other ethnic restaurants, many of the workers are immigrants who find short-term employment through an underground network. Their ability to speak or understand English may be limited or non existent. Working long hours, mostly on their feet, they earn minimal pay with no fringe benefits and are vulnerable to exploitation by restaurant owners. They may have left families back in China and send part of their earnings back to support them..

A 2014 article by journalist Lauren Hilgers provided an in-depth and sympathetic examination of the plight of "underground workers" in several Chinese restaurants in the New York City area. Inspired by Hilgers' article in New Yorker Magazine, another journalist, Katie Salisbury, herself the grand daughter of a Chinese immigrant restaurateur, interviewed Chinese immigrant restaurant workers for an online report in 2018.

Posted by John Jung. Posted In : restaurant workers

After retiring from a 40-year career as a psychology professor, I published 4 books about Chinese immigrants that detail the history of their laundries, grocery stores, and family restaurants in the U. S. and Canada.

After retiring from a 40-year career as a psychology professor, I published 4 books about Chinese immigrants that detail the history of their laundries, grocery stores, and family restaurants in the U. S. and Canada.